Sous-total: $

We Have Met the Enemy and It Is Us

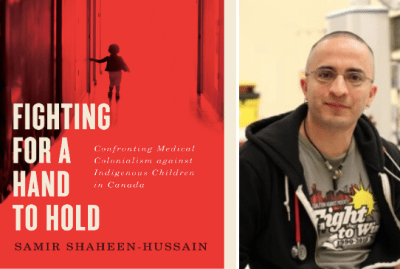

I borrowed the title above from Pogo, an old newspaper comic strip. To me, it conveys the sombre mood of a 1960s America at odds with itself. Anti-Vietnam War demonstrations, civil rights protests, and the assassinations of civil rights and political leaders forced a generation to question their nation’s underlying myths and lies. I thought it fit the mood of Fighting for a Hand to Hold: Confronting Medical Colonialism against Indigenous Children in Canada, a new book written by Dr. Samir Shaheen-Hussain. As he told me by email, he wrote this book “to make it simply impossible for anyone to deny any of this anymore.”

“This” is the medical establishment’s role past and present in, as Shaheen-Hussain explains in his book, a “longstanding history of systemic anti-Indigenous racism and medical colonialism, a term used to describe the violent and genocidal role played by the health care system in the colonial domination over Indigenous peoples.”

Fighting for a Hand to Hold begins with two Inuit children with serious injuries. They need emergency medical care that their small fly-in community cannot provide. The kids are bundled onto a medevac flight and rushed to the Montreal Children’s Hospital. At the airport, however, their parents are told they can’t be on that same flight with their kids.

Not for the first time, this raises concerns in the emergency room in Montreal. There is no translator. Dr. Shaheen-Hussain and others are worried that parental rights have been violated. What about the patient’s (or the parent’s) rights to give, and the medical staff ’s legal requirement to obtain, informed consent before any medical procedure? At the very least, wasn’t it just plain wrong to dump children in distress off to unfamiliar people a thousand kilometres from home, “many of whom would poke and prod them while speaking a foreign language”?

A few days later, Dr. Shaheen-Hussain and other doctors write a letter stating their objections and deliver it to the medical evacuation service and the person ultimately responsible: Quebec’s minister of health, Dr. Gaétan Barrette. The response from the minister is, to be kind, arrogant indifference. Weren’t things always done this way?

That’s the book’s starting point. From there it delves into historical context that makes indifference and cruelty by the medical establishment possible and predictable, supported by government regulations. This book takes us down dark corridors where both unintentional and deliberate racism are condoned by bureaucratic nonsense pretending to be government policy. The author jolts the reader from complacency page after page, detail after detail, pushing the reader beyond individual incidents to an understanding of a bigger picture. First, he writes, he must dispel “the commonly held belief that the medical establishment is inherently benevolent.”

There are stories we all know. Joyce Echaquan, an Atikamekw mother, screaming her last moments over Facebook Live before dying in a Joliette hospital as nurses spat racial insults at her. Brian Sinclair, an Anishinaabe homeless man, sent to emergency at the Winnipeg Health Sciences Centre for a simple change of a catheter. He sat ignored in a wheelchair for more than thirty hours until somebody noticed he was dead from an infection. The hospital said it was a “perfect storm” of administrative mistakes. But Indigenous peoples said what really killed Echaquan and Sinclair was a combination of old stereotypes and medical racism.

Incidents like this happen a lot. Not every one is recorded or broadcast live. Not every one results in an official complaint. If there is a complaint, Dr. Shaheen-Hussain said at an online panel discussion I recently monitored, it’s only “the tip of the iceberg.” If there is an investigation, such as those in Winnipeg or the Joliette hospitals, “they are called isolated incidents and not part of a much larger problem of systemic racism and discrimination in the medical establishment.”

“It’s nauseating. It’s ongoing and tragic,” he added. “It’s nothing short of inflicting medical violence.”

The incident with which the book opens started a petition that became a campaign by paediatricians like Dr. Shaheen-Hussain. That campaign is called #aHand2Hold. It led to calls for action, not words of denial or contrition. The objective was clear: to overturn the policy that prevents Indigenous parents from comforting their children on emergency medical evacuation flights to hospital. The campaign worked. Officially, parents would now be with their children on those medevac flights. Unofficially, Minister Barrette told pilots they could keep parents off those flights because of “agitation” or “intoxication” – euphemisms for drunken Indians.

Here’s the thing, though. That “official policy” at the root of this controversy never existed. It was a figment of racist imagination. It deemed some people less worthy of human compassion at best and was a virtual “Whites Only” sign at worst.

Like #IdleNoMore, #BlackLivesMatter, and the #MMIWG (Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls) movements, #aHand2Hold has evolved into a national concern, finding common cause with other social justice movements. Understandable, given the stonewall erected by Quebec about anything systemic trickling down to hospitals, clinics, child welfare agencies, schools of medicine and nursing, and so on.

This January saw a federal summit on Indigenous health with provincial and Indigenous leaders hosted by Indigenous Affairs Minister Marc Miller, a Montrealer. He’s in one of the toughest jobs in the federal cabinet, dealing with a colonial system, issues of lesser everything for colonized Indigenous peoples, and bureaucratic stonewalls from one end of the country to the other.

“We know going into the meeting that there is systemic racism in the health care system in every province and in every territory,” Miller said at a press conference ahead of the summit. “We know that it’s false to say that the federal government has no role to play in the health of Canadians. If anything, this epidemic has shown us as much. We also know that this is a jurisdiction zealously guarded by the provinces. But when it comes to issues like systemic racism and discrimination, every leader in this country has a leadership role to play.”

I learned this morning while writing this that a man from my home territory was discharged from a local hospital. The hospital staff didn’t deliver him to a caregiver or family, a pre-arranged medical transport, or a taxi, as required. He was discharged in winter wearing nothing but a hospital gown and socks.

Plus ça change.

Which brings me back to Pogo, and 1960s America torn by protest marches and riots. After deep national soul-searching, the result was a president’s order to overhaul federal laws, policies, and programs. Lyndon Johnson called his reforms “the Great Society.” Johnson wanted to make a better, more fair nation for all its citizens by tackling the twin evils of racism and poverty, reducing crime and reforming education, creating equal employment opportunity, extending voting rights and health care. The impact of these reforms is still felt more than 60 years later.

That was the United States then. This is Quebec now. According to Premier Legault, systemic racism doesn’t exist in provincial laws, policies, programs, or institutions. Nor does discrimination diminish the lives of Indigenous peoples, followers of Islam, Black and Brown peoples, LGBTQ2 people, and so on. Not much soul-searching going on here.

That’s okay. Because those who sit in that camp probably won’t read this book. But everyone else probably should.

Taionrén:hote Dan David is a recovering journalist, aspiring writer, and habitual windmill tilter. He is based in Kanehsatå:ke, a Kanienke:haka (Mohawk) territory near Oka.

Taionrén:hote Dan Davi, Montreal Review of Books, printemps 2001

Lisez l’original ici.

Mon compte

Mon compte