Sous-total: $

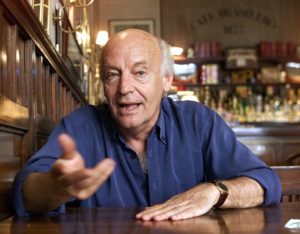

A World Cup Without Eduardo Galeano, Soccer’s Poet Laureate

As the 2018 tournament kicks off, it’s worth revisiting the late Uruguayan writer’s classic book on a sport he approached as both a fan and a social critic.

At the 2018 World Cup, which began in Russia this week, the United States will be absent, as will Italy—and as will Galeano, who died of lung cancer in 2015. But he lives through his writing on the sport. To read Soccer in Sun and Shadow today is to commune with Galeano’s spirit, to hear his fierce, tender voice alive with passion and indignation about the beautiful game. “I wanted fans of reading to lose their fear of soccer,” Galeano wrote for The Washington Post in 2009, “and fans of soccer to lose their fear of books.”

As a boy, Galeano loved football, but he didn’t play well. “By writing,” he explained in Soccer in Sun and Shadow, “I was going to do with my hands what I never could accomplish with my feet.” And so he drew political cartoons as a teenager and went on to become a journalist, a newspaper editor, and a celebrated social critic. His pioneering 1971 book, the anti-colonial, anti-capitalist Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, implausibly landed on Amazon’s bestseller list in 2009 after Venezuela’s president, Hugo Chavez, gave President Barack Obama a copy, calling it “a monument in our Latin American history.” (Despite its influence, Galeano appeared to renounce the book later in his life.) In the 1970s and ’80s, Galeano was forced into exile in Argentina and then Spain by Uruguay’s right-wing military regime. During that period, he wrote most of his ingenious historical trilogy, Memory of Fire, an epic retelling of 500 years of conquest, myth, and rebellion flecked with humor and invective.

As a literary writer on sports, Galeano is akin to Norman Mailer, who found poetry and politics in boxing; but where Mailer was inclined to fight, Galeano leaned toward love. His inimitable style was to write his narrative in vignettes (“story windows” he called them)—concise distillations of grand events and ordinary goings-on. The story-window approach runs all through Soccer in Sun and Shadow, which moves chronologically across the fractured history of the sport—from a Chinese leather ball filled with hemp in 3000 B.C.E. through news crawl–style reports of modern World Cup matches. Pelé, Diego Maradona, and Franz Beckenbauer make cameo appearances, too, scoring famous (or infamous) goals.

An instinctive social critic, Galeano saw soccer as a pitched battle between good and evil, a choreographed war in which “11 men in shorts are the sword of the neighborhood, the city, or the nation.” On the pitch and in the stands, “old hatreds and old loves passed from father to son enter into combat.” Local roots run deep and unite and divide fans, and whole nations, accordingly. Soccer’s participants are archetypal figures. The goalie: “Whenever a player commits a foul the keeper is the one who gets punished: They abandon him there in the immensity of the empty net to face his executioner alone.” The referee: “Everybody hates him.” The manager: “His mission: to prevent improvisation, restrict freedom, and maximize the productivity of the players.” For Galeano, the struggle for power was everywhere. About Argentina’s Maradona being expelled from the 1994 World Cup for having ephedrine in his urine, the writer remarked: “Maradona committed the sin of being the best, the crime of speaking out about things the powerful wanted kept quiet, and the felony of playing left-handed.”

Soccer, in Galeano’s vision of it, isn’t just a war between teams or countries: It’s also a war between humanity and technocracy. He called himself “a beggar for good soccer” and in later years found himself frustrated by the hyperprofessionalization of the sport, which “negates joy, kills fantasy, and outlaws daring.” He saw the influence of corporations (with their logos emblazoned upon the players’ uniforms) and the power of television executives to determine “where, when, and how soccer will be played.” Such standardization, he argued, caused players to “run a lot and risk little.” Readers can hear his indignation rise as he writes, “Audacity is not profitable.” Although cancer kept him from writing about the 2014 World Cup, Galeano watched as Brazilians took to the streets to protest the lavish spending on new stadiums rather than on education and infrastructure. In a statement released the year before the tournament, he said that the Brazilian people “have decided not to allow their sport to be used any more as an excuse for humiliating the many and enriching the few.”

What would Galeano have said about the present World Cup, hosted by a country (Russia) run by a strongman (Putin)? Or about the 2022 Cup, set in a desert country not known for soccer (Qatar), or the 2026 Cup hosted by three countries in the middle of a trade war (North America)? Surely he would have been stirred to high dudgeon; and yet surely he would have been exhilarated by the prospect of Friday’s Game 2, which pits his native Uruguay against Egypt—a match-up rich with the villains and heroes he loved to write about.

For Uruguay, there is the diabolical striker Luis Suárez, who illegally batted Ghana’s ball out of the goal in the 2010 World Cup, vaulting Uruguay into the semifinals. Galeano, ever the contrarian, defended Suárez’s “act of patriotic madness,” seeing it as a vestige of garra charrúa—the fighting spirit by which the country’s Charrúa tribe fought foreign occupiers. At the 2014 World Cup, Suárez famously bit Italy’s Giorgio Chiellini, prompting much derision, and the creation of a novelty bottle opener shaped like Suárez’s open mouth. Suárez’s foil today is perhaps the humble hero Mohamed Salah, who lifted Egypt into its first World Cup in 28 years, all while leading Liverpool into the Champions League final.

It’s easy to imagine the ghost of Galeano sitting in that favorite chair watching this match, his heart open wide. He was soccer’s own literary rascal, writing with abandon, audacity, and a childish passion for combat and play.

Though Galeano relished each World Cup, after each he also felt spent and sad. In an updated epilogue to a 2013 edition of Soccer in Sun and Shadow, he wrote of the loss he experienced at the end of the 2010 tournament:

I miss the celebration and the mourning too, because sometimes soccer is a pleasure that hurts, and the music of a victory that sets the dead to dancing sounds a lot like the clamorous silence of an empty stadium, where one of the defeated, unable to move, still sits in the middle of the immense stands, alone.

Lenora Todaro, The Atlantic, 15 juin 2018

Photo: Uruguay fans in Montevideo in June 2018. Andres Stapff / Reuters

Lisez l’original ici.

Mon compte

Mon compte